NBC Nightly News got it wrong about California’s solar situation with their July 8 segment titled “California’s Unexpected Energy Challenge: Too Much Solar.” Correspondent Liz Kreutz used these provocative but completely inaccurate visuals and spoke of California “losing” or “wasting” energy. How our national media could get this so wrong was shocking – so much so that I was motivated to write this piece. Unexpected? No, the challenge of managing supply and demand of electricity with increasing renewables is a known issue called “The Duck Curve” that California has devoted extensive research to. Too Much Solar? No, we’re going to need more solar, more wind, and more batteries to store it as we move toward an emission free electric grid by 2045, as required by the SB-100 bill passed in 2018 by the California legislature and signed by the Governor.  At one point, correspondent Liz Kreutz asks Eliot Mainzer, CEO of CAISO, California’s main grid operator, if curtailment means “throwing solar power away.” He disagrees, explaining that curtailment involves sending dispatch instructions to reduce generation. But Mr. Mainzer missed the chance to deliver a full-throated defense of clean energy. Curtailment is not waste; it’s an inescapable truth of generating electricity from renewables. There are times when we have more power than we need and times when we need to turn to other sources like battery storage and gas power plants. Saying that we are “throwing solar power away” is like saying buffet restaurants need to be banned because they sometimes make more food than customers want to eat. The point that the national news missed is that, even factoring in the times when solar power plants make electricity we can’t use, solar power plants are less expensive ways of growing our electric grid than all other options. Growing our grid is what we’re going to be doing for the next few decades to supply EV charging and all-electric buildings with cleaner and cleaner power. When we pair solar generating facilities with battery storage, we have a more cost-effective source of new electricity than building new gas power plants, and solar plus battery is just as reliable! Recent studies by U.C. Berkeley, Princeton, and the California Energy Commission show that our grid CAN provide reliable electricity using 90% or more clean emission-free generation sources like solar, wind, and batteries. And we can do it without increasing utility costs while realizing significant public health benefits from reducing fossil fuel-related pollution. While we are already at about 60% clean energy, we still have a lot of work left to do. This is going to be the defining challenge of our generation – transitioning our buildings, vehicles, and electricity grid of fossil fuels to renewable and clean sources including nuclear and hydropower. It’s going to take all of us pulling together in the same direction to be successful on this huge challenge, so misinformation like this story is unhelpful; this is why I felt the need to correct it.

0 Comments

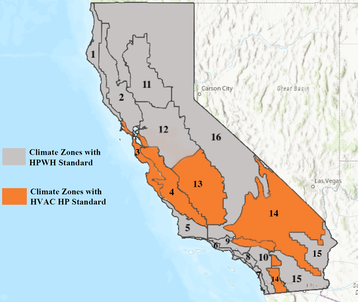

In the homes we grew up in, we all happily ran our homes and businesses on tank water heaters. We found room for them in interior and exterior closets and the corner of the garage. But then came tankless water heaters and their promise of never-ending hot water. You could bolt them to the wall too and take up no floor area. The 2013 California energy code gave us such a big compliance credit for putting a gas tankless water heater in our designs that high-performance walls and -attics were the standard but completely avoidable. Ever notice that tankless water heater manufacturers have Japanese names? Rinnai, Takagi, Noritz… That’s because tankless water heaters were created in Japan to solve a very Japanese problem – no space for a tank of water in dense city apartments. Once Americans saw them, they had to have them too; we suddenly acquired a new-found need for unlimited hot water. They were marketed smartly as energy savers [look, there’s no wasted energy keeping that tank full of water hot!], but at 200,000 btu/hr, they are like taking a machine gun duck hunting – overkill. The past few years in California, gas tankless water heaters have been the standard in new homes and remodels. Enter climate change and the need to reduce Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions. Our modeling software proves that HWPHs have 80% lower GHG emissions and 50% lower energy use than gas tankless.[1] This is the single biggest thing you can do to bring down overall home GHG emissions. We now realize that heating our homes and our water with gas is a luxury we can no longer afford. California has appropriately realized that electric heat pump water heaters are the right system for almost every project – efficient, quiet, and more than capable of supplying all the hot water a family might need. There’s just one catch – they are tank water heaters, and require a 3’ square footprint. [1] Modeling based on new code-compliant 2-story 4 bedroom home in Inland Empire Southern California (CZ10) on 2022 CBECC-RES software comparing typical efficiency gas tankless (uef 0.81) and typical efficiency HPWH (3.5 COP) in garage. So how do we transition the California market from gas tankless water heaters to heat pump water heaters, now that we are addicted to the idea that we need never-ending hot water? It starts with realizing HPWHs are a whole lot more efficient than the old tank water heaters we grew up with (the tanks are so well insulated they lose ~4 degrees over the course of a day) and we can always find a closet or corner of the garage to put them in. Next, we need to provide training to the trades, builders, and architects on how to install them without problems. In single family homes, they can go in the corner of the attached garage or in a closet with a louvered door. In multifamily buildings, each unit can get one in a closet or they can be piped together to serve as a central system. New tools like Ecosizer are helping design such systems.

The time is now, because the climate crisis cannot be ignored and we can’t continue installing gas systems today when we know better and what we build today will operate that way for 10+ years. PLUS, there is incentive money in the TECH Program to encourage the gas-to-heat-pump water heating transition -- $3,100 for every Californian in PG&E, SCE, and SDG&E territories to replace their gas water heater with a HPWH. The 2022 California energy code took a few steps in the right direction to encourage this transition:

So take the money and run your house’s water heater on electricity. And take advantage of all the training offered by your utility, the water heater manufacturers, and Energy Code Ace, because heat pump water heaters are coming in hot! Are you a builder or developer who is working on a new construction project? If so, the Energy-Smart Homes All-Electric or Mixed Fuel Residential Programs could help you lower your project costs. These programs were created to support California’s energy efficiency policy goals and help mitigate climate change. Energy-Smart Homes Program At A Glance

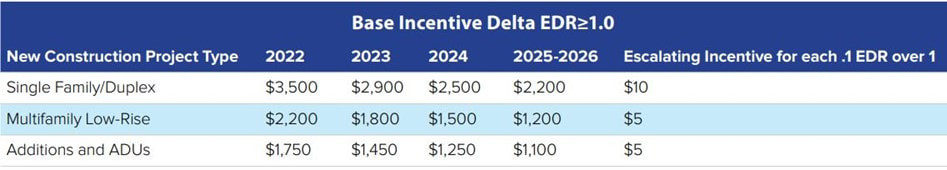

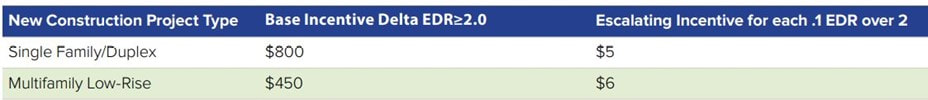

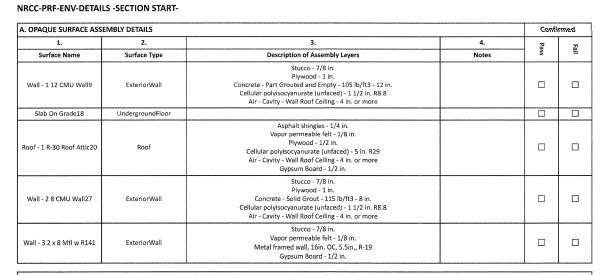

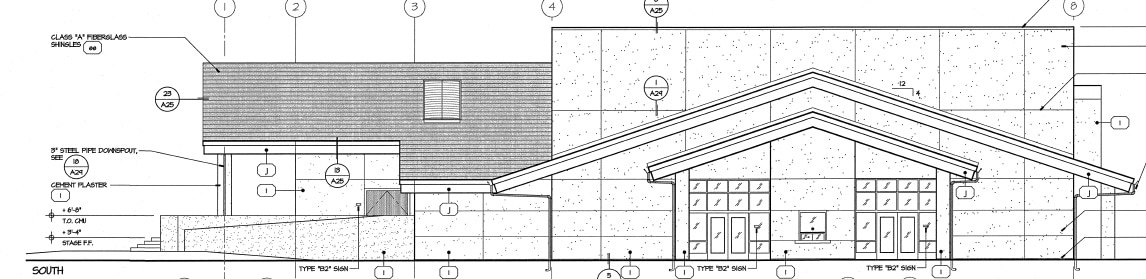

What are the eligibility requirements? Both programs serve new single-family residences and duplexes, manufactured housing, multifamily low-rise buildings (three stories or less), and accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Participants must be customers of SDG&E, PG&E, SCE, or SoCal Gas and the builder/developer must pay the Public Purpose Program Charge. All new construction projects are required to install communicating thermostats, segregated circuits, battery storage readiness, thermostatic mixing valves, and electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure pre-wiring in accordance with CALGreen Building Code EV ready requirements. All new construction projects must also achieve an efficiency EDR of greater than or equal to one EDR point above standard in their Title 24 compliance for the All-Electric program and two points above standard for the Mixed Fuel program. There are no incentives for solar measures, so eligibility is determined by efficiency EDR only. To satisfy this eligibility requirement your Title 24 compliance must be completed by a CEA. If you are interested in this program and in need of a Title 24 consultant, contact us! We are CEA certified and happy to help you with the compliance process. What kinds of incentives are there? Incentive amounts differ depending on the type of project and year of completion. The incentives are paid on an escalating scale with a bonus incentive for each additional 0.01 EDR above the entry requirement. Base incentives de-escalate 10% annually based on completion year in the All-Electric program. Incentive amounts for new construction in the All-Electric program are listed below. The incentive amounts for new construction in the Mixed Fuel program are listed here: Case Study: All-Electric New Construction To see what kinds of incentives a project would be eligible for, we will look at a real, all-electric, new construction project. Our case study is a 2,000 sq ft single family home in Climate Zone 11. It has a central split heat pump, a heat pump water heater, and all-electric appliances. The project has a Title 24 compliance delta efficiency EDR of 4.1, meaning that it surpasses the required 1-point difference. Assuming this project is to be completed in 2022, it would receive $3,500 in incentives, plus $10 for each 0.1 EDR points over the required delta of 1. This means it would receive $3,500 + ($10 x [3.1/0.1]) or $3,810 total. How do I apply? Before you start the application process, make sure your project meets all the eligibility criteria. Part of that is getting your Title 24 compliance done by a CEA (like us)! Contact us and we will get back to you with a quote. Once you have determined you are eligible, you can start the application process by logging in to the participant portal (https://CAenergysmarthomes-OLA.Capturesportal.com) and setting up an account where you can submit application documents and a program participation agreement. If needed, you can also contact Energy-Smart Homes staff at [email protected] and they will assist you with your application or complete the inquiry form at www.caenergysmarthomes.com to have an Energy-Smart Homes representative follow up with you. I recently assisted the project team on a new school gymnasium building in Tipton, which is in California’s Central Valley. The project was approved and going out to trades for bids, and the plastering contractor had concerns that the building could not be built as it was drawn. The walls were made from concrete block, and in order to get the building to meet the California energy code, the energy consultant selected a continuous layer of R-9 Polyiso insulation board at 1.5” thick over the block, with plywood and stucco over that. This wall system cannot be built. There is no possible way to apply Polyiso to the concrete block, then apply plywood and stucco over the Polyiso. The problem was this … the building energy usage was modeled with this R-9 continuous insulation layer, for a wall U-factor of 0.070 with 8" and 12” thick concrete blocks. The insulation helped the building comply with the energy code by reducing energy usage to compensate for energy used elsewhere in the building. So the team building the gym could not substitute out another wall system with a higher U-factor and still meet the energy code. When we met all together to discuss the issue, the builder, architect, plasterer, and HVAC engineer were all present. We defined the problem and proposed alternative wall systems that would meet the same U-factor. Metal Z-furring was proposed to provide a mounting mechanism for the plywood and stucco over the foam. But the wall would have leaked energy through the Z-furring, and this would not meet the specification for a continuous layer of R-9 insulation. We found that R-9 between Z-furring would have produced a U-factor of 0.384, which is not even close to the U-factor used for compliance. So we turned to the ideal wall system for continuous insulation … EIFS. EIFS is an adhesively attached system, so fastening into the concrete block is not necessary, and the stucco is adhered directly to the foam board. We found that an EIFS system with R-9 or greater insulation would meet the overall U-factor used in the modeling, whether it used Polyiso at 1.5” or Graphite EPS at 2”. How did we end up with this problem? The energy code has become complex enough that energy consulting is a specialized job with an association in California to govern the industry, CABEC. But many projects ask the mechanical engineer to handle the Title 24 paperwork. What they don’t realize is that the Title 24 energy code provides for many alternatives to comply, and allows for tradeoffs between insulation, windows, mechanical systems, water heating, etc. So to ask the mechanical engineer to run the energy models is unrealistic and probably limits design options today for any project with any complexity. And that’s what happened on this project. Gymnasium buildings need ventilation for full occupancy. To accomplish this requires large fans, which use more energy than the commercial standards allow for. So these type of buildings require energy savings in other parts of the building in order to reach compliance. In this case, higher insulation values in the walls were used to save on heating and cooling to compensate for ventilation energy. This is what we do – help building designers keep energy efficiency at the table, as key design decisions are made. And we help them navigate the increasingly complex set of regulations known as Title 24 in California.

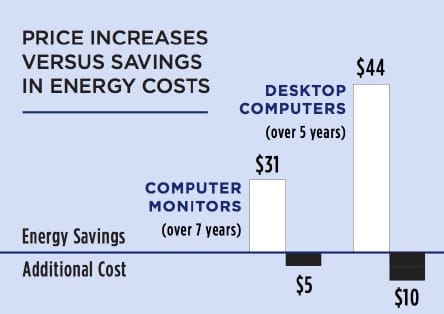

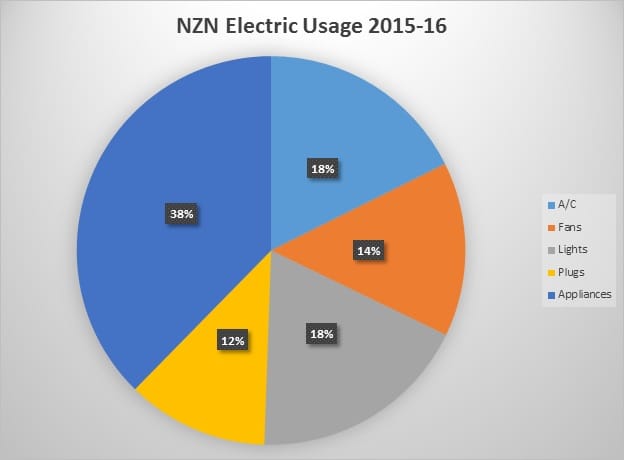

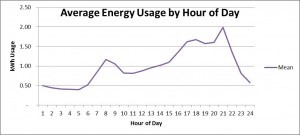

In one of the first moves of its kind, the state of California has enacted energy efficiency standards for computers and monitors. If the state that is home to Silicon Valley can take this step, an other state interested in reducing energy use could be safe to follow its lead. The new standards are estimated to save $370 million a year or 3-7% overall energy use in the state. The details are that the standards will be phased in from 2018-2021, with different standards for laptops, desktops, servers, and monitors in several categories. Chief among the new requirements are idling caps on energy use when not in use. The monitor standards have a payback of 600% over 7 years, and only 14% of current monitors would comply with the new standards. Desktops have expected payback of 400% and laptops 200%. This move shows what California has learned from its drive to tamp down energy use (and energy waste) toward its goal of netzero buildings -- the more you design in energy efficiency in the building envelope and mechanical systems, the more the "plug load" takes over as the low-hanging fruit for additional energy savings. In the net-zero home we built, for instance, fully 12% of total electric usage was plug load (see chart below). And that energy is often easier to reduce than heating, cooling, and lighting, once efficient HVAC, appliances, and LED lighting have been installed inside a tight envelope. By 2020, all new California homes are required to be net-zero. There are many definitions of net-zero, but the one that counts for the California energy code is TDV net-zero.

Think of TDV as a weighted average. The modeling software used to prove compliance with the energy code weights every hour's electric usage by the cost to produce that power in your climate zone. So peak periods count FAR MORE than non-peak periods. This means that west-facing windows (which take on heat in summer during peak periods for the utilities) get penalized more heavily than north- or east-facing windows, and in most cases south-facing windows. To give you an idea of the TDV factors, the 2016 standards have TDV factors that average 20 kbtu/kwh. Some days in August and September have TDV factors as high as 500 or 600. This is how the utilities bring the reality they deal with every day of peak production loads into the equation, and it makes sense. The energy code actively discourages designs that worsen the need for peak production, which typically is the most expensive and dirty electricity production. Now that you know what TDV is, you can understand that TDV net zero is a less stringent goal than the purest definition of net-zero, which is site net-zero. In site net-zero, a boundary is drawn around the property. The sum of what goes in is less than or equal than the sum of what goes out. If you produce as many btu's of electricity with your PV panels or wind turbines or hamsters in cages as you pull off the grid during the year, you're net-zero site. By using TDV factors and applying them to the grid energy used, the calculation weighs the on-site production more heavily than the grid energy used. Why? Because grid energy has emissions associated with it and other societal costs, whereas on-site renewable energy production does not. Also, PV panels produce a lot of their energy during peak periods, and grid energy is often drawn off-peak in a net-zero home. Bear with me; I'm getting there! Our net-zero TDV house is about 65% net-zero site. That is, we produce about 65% of the energy we use by a site definition. That will be enough to qualify as a net-zero house by the 2020 California Energy Code. If you use all electricity in your home, the calculation is easy. But what if you're a "dual fuel" home, with gas and electricity? In that case, we convert the natural gas usage to equivalent btu, do the same with electricity, and do our math in btu's. The TDV energy produced by the PV panels has to more than equal the TDV energy used by the gas systems and electric systems in the house. Hope you're still with me, because I'm just now getting to the point. Most net-zero houses are more economical to build "dual fuel", because gas is the most established and efficient way to heat a home and dry clothes and heat water in most areas of the state. In our case, 60% of our annual energy use is from natural gas; we would have needed an additional 4-6 solar panels to reach net-zero all-electric than the way we did it -- dual fuel. What's this mean? Most net-zero homes will produce more electricity than they pull off the grid. Our house had a surplus of over 1,000 kwh electricity in its first year of operation. This is partially compensating for all the gas usage in the house. And our electric utility pays us poorly for these excess kwh -- about 4 cents each last year. This is what makes an electric vehicle look attractive to a net-zero dual-fuel home. They will find they have excess electric production, purchased by their local utility at very low rates, and will look for options what to do with it. They could do wasteful things with it, like adding a big freezer in the garage or running their A/C more in summer. Or they could use it to cheaply power an electric car. Whatever they have in extra production will cost them $0.01 per mile or thereabouts, as compared to about $0.10 per mile for a typical gas car. Net-zero + Dual-fuel = EV With so many variables, it’s hard to decide on an EV. Here’s what we grappled with in our decision to (Spoiler Alert) lease a 2016 Nissan Leaf:

1.Range anxiety (at 110 miles per charge, is that enough for our family?) 2.Understanding federal and state incentives 3.Degradation in battery life over time – how real is this? 4.Drive-ability 5.Room for 5 people comfortably? 6.Newer models coming out (Tesla 3 and Chevy Bolt) 7.Cost of operation vs gas vehicle 8.How do you install a charger (EVSE) in the garage? 9.How much could we use our solar panels to charge it versus off-grid power? 10.Are those HOV stickers still available in California? 11.Lease vs buy 12.Hybrid vs Pure EV And here is what we found out and decided: 1.Range anxiety is real but do-able with planning ahead At 110 miles, that’s 50 miles each way with a 10-mile cushion. Luckily stop-and-go traffic seems to help EVs, since they regenerate some energy during braking, the opposite of gas cars. So the 10-mile cushion seems fairly safe. With the ability to trickle charge at your destination, that can add 5-10 miles per hour, and that’s possible with a standard 110V outlet and the free cable that comes with the car. With a 240V Series 2 charger on the other end, you can add 20 miles per hour to your battery and really extend your range. And if you plan around a DC charger, such as most Nissan dealers have, you can go 80+ miles, get an 80% recharge in 30 minutes and head home. So for us, we have a gas car for long trips and we will use the EV for all around town and mid-range trips of 50 miles or less, 80 miles or less with ability to charge on the other end. 2.Federal and state incentives The dealers were offering $7,500 federal rebates, and $2,500 state rebates in California, although the state money was contingent of renewal of the program, so we couldn’t take that for granted. By leasing, the $7,500 was rolled into the deal, along with other dealer incentives that pushed the capital cost reduction well over $10K. We’ll hope to get the state rebate, too. The government continues to do its best to give EVs a start in the market dominated by internal combustion engines. 3.Degradation of battery life over time The research we made showed we could expect 70% battery life after 5 years or so, and that charging behavior is a key determining factor in this. Just like a cellphone battery, if you charge it often, the battery loses its ability to hold a charge faster. So we’ve been trying to run it down under 50% before recharging. But if we have a possible trip the next day, we’ll have to top it off in the garage. With a lease, this is not a large issue. 4.Drive-ability This is answered by test driving, and your local dealer would love you to do so, because they’re so convinced you’ll be hooked that you’ll probably get one. They really are a joy to drive. The big difference I noticed right away was acceleration. There is no delay between putting the pedal down and the engine responding, so it’s peppy. Acceleration on the freeway onramp is scary easy. And the Leaf handles turns and braking nicely as well. I’ve never been so excited about driving a new car as this one, and I’ve probably driven a dozen new cars over the years. 5.Room for 5 people Because they have to count their pounds like the Weight Watchers of car designers, EVs are not as roomy as their gas cousins. But I found the Leaf had plenty of room for 3 in the back seat 6. Wait for new models or pull the trigger now? We had a career change that made this decision for us. And the 3-year lease gives us a timetable to get to where the new Teslas, Chevys, and Nissans have worked out some bugs and extended range on affordable models to 200+ miles. Then our next EV can be all the car we’d ever need to go between LA and San Francisco with one stop or go to the mountains. But if I had a car with 2 years left in it, I would have run it into the ground and waited for the next generation of EVs. 7.Cost of operation This breaks down into gas vs electricity cost and maintenance and insurance cost differences, if any. Let’s assume we’re getting 3.8 miles/kwh on the Leaf (which we are). At $0.20/kwh, that’s about $0.05/mile. A comparable gas car might get 30 miles per gallon on $3/gallon gas. That’s $0.10/mile (double). Plus, maintenance should be much less for an EV, with fewer moving parts under the hood. And insurance on the Leaf was less than our other cars. So we stand to save $750/yr on gas alone at 15,000 miles/yr. 8.Chargers 101 You don’t call it a charger, first of all! The EV community seems pretty stubborn about calling them EVSE’s. So we’ll have to go with that until a TV show character gives one a cooler name. For now, I’ll call it a charger. I found some for $300, but ended up getting a Clipper Creek one for $600 that everyone swore by. I had a 30 amp RV plug at 240V already on the back of the garage, and planned to use that. But that could only handle the 24 amp charger. The 32 amp charger would make a big difference in charging speed, so I had my electrician upgrade the breaker to 40 amps and ran a new line in the garage. It is charging from nothing to full in about 5 hours. The brains of the whole charging thing is in the car. The car knows when to turn off the charger. The car can set a timer to turn on and off at a certain time to take advantage of off-peak electric rates. All you need that EVSE to do then is safely move the current. You might spend your first year’s gas savings on an EVSE and installation. 9.Using solar power to charge the car We have an excess of solar PV capacity on the roof of about 1,000 kwh/year, or 3,800 miles per year worth. The utility pays us $0.04/kwh for that power, as part of our net metering agreement, so that’s a bum deal. We might as well use it for an EV. That means the first 3,800 miles per year are at $0.01/mile. Then we start paying Tier I rates from the utility. But, even in the middle of summer in the middle of the day, when our PV panels are maxed out, they only produce 4 kw, and the charger uses 6.6 kw, so we can’t charge at full blast without help from the grid. All that comes out in the end-of-year wash, when the utility calculates what we took versus what we returned to the grid, regardless of what time of day it was. Net metering is a good deal for the consumer, who gets to use the grid whenever their panels can’t power them as a virtual battery, and just clear up their account at the end of the year, like those general store owners used to do in all the Westerns when the farmers sold their crops for the year and bought their wives and daughters fabric to make dresses. 10.HOV stickers in California We wanted one of those mud flap stickers like on those Priuses when they first started strutting their environmental superiority over our gas cars 15 years ago. But we also heard those stickers aren’t available any more. Well it seems that’s true, for hybrid EVs (check your specific model at the DMV website). But for our ZEV (zero emission vehicle), they have a shiny white HOV lane sticker available by mail for $22, once you get your registration in the mail. And until then, you can drive the carpool lane with impunity since you have no plates; just watch for the highway patrolman. 11.Lease vs buy We bought our solar panels when leasing them would have been easier, so we’re not lease lovers. But with the longer range models coming online in the next year or two, and the dealers’ willingness to take all the uncertainty and paperwork out of the federal rebate process for us, and a sub-$300/month lease on offer with a reasonable downpayment, we decided on the 15,000/mile a year lease. 12.Hybrid vs Pure EV A plug-in hybrid seems like the perfect compromise … the economy of an EV driving around town near home with the range of a regular gas car. But we just wanted to make more of a statement than that … that we can plan around limited range and charging stations to make an electric vehicle with no emissions work. And why spend an extra $2,000 or so to have a redundant engine under the hood – that’s not a no-cost compromise. My wife and I just have come to believe through our research that the natural gas plant down the street can burn gas and make electricity and get it to our house to charge our car more efficiently than the oil companies can get gasoline to the gas station by way of the refinery by way of the ship from the Middle East for my gas engine to burn. And if 30-50% of the power comes from my rooftop solar panels or solar panels in the Mojave Desert or hydropower, then I think that makes a pure EV make good sense now and, even more so, in future. In 2010, we wrote: "The updated California energy code is changing the insulation and plaster systems being used throughout the state." We said it then and we have to now say it again, and this time the impact of the 2013 California Energy Code standards will be much more significant than the last cycle. This is because the new code requires significant upgrades in the insulation of wall systems. For the past few years, residential standards for wall systems in much of the most populated areas of the State were status-quo, and commercial standards were done by measuring the effective insulation value of the entire wall system, taking into account thermal transfer through framing and windows. This overall approach to wall insulation now comes to residential construction with the start of the 2013 standards in July, 2014. This represents a paradigm shift in how exterior walls of residential structures will be built in the State Climate Zones Climate Zones played a big role in the residential wall requirements in the past edition of the energy code; not so now. All climate zones now require an overall wall U-factor of 0.065. That translates into an effective R-value of about 15, taking into account the leakage through studs called thermal bridging. To comply, many new homes will be built with continuous insulation, a method in which foam board is installed outside of the framing in a continuous sheet, with the exterior cladding installed over it. It is important to understand that tradeoffs between systems are allowed. As long as the house will use the same amount of energy as the specified designs, you can trade off insulation against windows, HVAC systems, etc. How Are Builders Complying? In order to comply with some of the stricter requirements under Title 24, continuous foam insulation (CI) is becoming more common. The use of foam panels applied outside of the studs necessitates the use of a plaster system specifically designed for use with foam panels. Commonly known as “one coat stucco systems” or EIFS, these plaster systems can achieve insulation in the wall system that is equivalent to Title 24 requirements or better. For instance, a home in Palm Springs could choose to use R-21 insulation between 2x6 wood studs, spaced 24 inches on center, OR R-13 batts between 2x4 wood studs with 1-1/2 inches of foam board and an insulated plaster system. See Table 1 for more details on residential CI systems. In commercial buildings using metal framing, the reasons to use CI systems are even more compelling. Because metal studs permit the transfer of more energy out of the building, their performance is improved more than wood-framed buildings by the use of foam insulation outside the studs. It would be difficult to comply with Title 24 building with metal studs without foam insulation in many climate zones, unless other significant energy upgrades were made in other parts of the building. For instance, building with a CI plaster system in San Francisco, Los Angeles, or San Diego, a builder can achieve Title 24 compliance with 1-1/2” of CI foam over 4” metal studs and R-11 batt insulation. See Table 2 for details on code-compliant CI systems for commercial structures.

Metal-framed hotels and high-rise residential have the same standards throughout the state. A U-factor of 0.105 is required, which can be met with 1 inch of CI foam over 4” metal studs with R-13 batts. Over wood framing, half the state allows a U-factor of 0.059, which can be met with 2x6 studs, R-19 batts, and R-4 CI. The most extreme zones of the state require U=0.042, which requires 2x8 studs. See Table 3 for details for use with hotels and high-rise residential projects. If you’re like us, you barely noticed the installation of a Smart Meter at your house in 2012. Our utility, Southern California Edison, installed them systematically across Long Beach with the stated goals of:

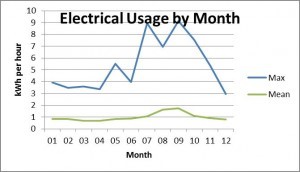

We thought we might take Edison up on the offer to access our usage data and see how useful it is. We logged into our account and downloaded the hourly kWh used for the last 12 months – over 8,000 data points in all. It helped us see the times of year and times of day that we use most electricity in our house, and showed exactly how large our spikes can be. Add our spike to our neighbors’ around Southern California, and you see how hard it must be to manage the grid in Summer without outages. Some of our takeaways were:

The data made us face some hard facts about our lifestyle. First, what are we doing at 9:00 at night in Summer? Watching TV, running the dishwasher, and cooling off the house with the air conditioner. Why don’t we open the windows? I don’t know. How much electricity does our TV use anyway? So we got out a gadget still in its wrapper that I gave my wife for Christmas – a Kill a Watt. It plugs into the wall socket and accepts the plug from another electric appliance and measures the electricity usage. Here’s some of what we’ve found so far:

We have yet to measure the usage of our A/C unit on the roof, or any of our major appliances, but they’re next! And if you’re considering putting solar panels on the roof and generating all your own electricity, your Smart Meter data will tell you what size array you need. In our case, a 3kW array would cover our daytime needs most of the year, but on the hottest days in Summer, we sometimes would need twice that to power the house. It will be interesting to see how the Smart Meters will be used in future. Perhaps they will communicate with our appliances to run when rates are low on off-peak times. I’m hoping that the utilities use the data to help homeowners discover if they are about average or using more than their neighbors, as this information is nowhere to be found today. I’m not interested in guilt-tripping anyone, but if it wakes a few households up that there are savings to be made, well that would be a good thing. Aggregate that over Southern California, and that could add up to power-plant-size savings. So far, I'm high on Smart Meters. Long Beach Encourages Homeowners to Go Native With the Innovative Lawn-To-Garden Program The Long Beach Water Department has an easy, affordable way to convert your gluttonous grass front yard and parkway into a water-wise wonderland. Long Beach will pay you $3.00 per square foot to rip out your lawn and replace it with native, low water landscaping. My husband Nick and I accepted the challenge at our home, which had a rarely used, somewhat sparse front lawn and parkway. Long Beach makes the process surprisingly easy. And despite our novice landscaping skills, the results are beautiful. Trust me, you can do it too. The first step is to file an application with Lawn-To-Garden, which we submitted on-line in a matter of minutes. The application itself is easy - you just need your water account number and the square footage of grass you are replacing. Next we received a letter in the mail telling us our application was approved and we had 45 days to submit our garden design. This is the reality check in the process – are you actually willing to do the work? Lawn-to-Garden has a lot of resources available, so you don’t need to hire a professional landscaper. You start by taking a short mandatory landscaping class (either on-line or at the water department). Then, you review the list of approved plants and other requirements and make a drawing. My husband and I looked at all the on-line examples, grabbed some graph paper, and went to work. Our drawing was crude, but accepted without ridicule. Then we waited… A few weeks later we received a letter saying our stick figure drawings were approved and we had 120 days to construct our new garden. Step one is to kill your grass. Since ours was already parched, we were in good shape. We hired the incredibly strong Miguel to dig up our remains and fix our sprinklers, which we converted to low flow rotator heads. In the meantime, I showed our plans to my friend Leslie Grenier, a professional landscaper and extremely generous person. She gently suggested a few changes to our design with phrases like “I consider this a freeway-quality plant.” Yikes. We ran the changes by the Lawn-To-Garden folks who didn’t even raise an eyebrow at the fact we were tweaking our design with two weeks to go. I am sure they’ve seen it all. Then we started visiting nurseries to collect the plants and mulch. Seeing all those shades of green and beautiful flowers lined up in front of our house made me realize low water does not mean boring and monotone at all. And in one very long day, Nick, Miguel and I did it – planted over 120 plants in our front yard and parkway and mulched every one. We even had our first butterfly – a perk of going native. We emailed the city, they came and inspected, and we passed. Glorious victory! Joyce Barkley, Long Beach Water Conservation Specialist, told me there are more than 500 Long Beach homes currently in various stages of the Lawn-To-Garden program. The funding comes mostly from a refinanced bond and the program is accepting applications. According to Joyce, the Water Department “expects to see an average water savings of 30% per single family household” that converts to a low water garden. At our home we reduced our water usage by 9 hundred cubic feet in the first partial-year alone. Joyce hopes the program will help change the perception that lawns are beautiful. I am definitely a convert. I feel like my new front yard has a wonderful organic quality that evolves and changes with the seasons. And converting a lawn is a tangible, important step towards responsible water conservation. It feels good to do our part.

For us, Lawn-to-Garden covered about ½ of the cost of replacing our lawn. Our expenses were split about evenly between Miguel’s time and plant/mulch/paver materials. If we were willing to dig out our own grass, we would have come close to breaking even (unless Leslie had charged us what she is really worth). More importantly, Lawn-to-Garden made the process simple. They were constantly available for questions, were flexible with our changes, and really did provide all the on-line resources we needed to succeed. For more information, check out www.lblawntogarden.com. |

AuthorNick Brown, CEA Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed